By Lindsay Mumma, DC

You have a training partner who is the same age and weight as you; you log the same number of miles per week, do the same cross-training, run the same hills, and take the same amount of time to warm up and cool down. So why does she not have the same “overuse” injury that you do? Achilles tendonitis, “runner’s knee,” IT band syndrome – they’re all “overuse” injuries, and the typical treatment plan includes rest, ice and some anti-inflammatories or stretching. But that doesn’t answer the question: Why would two identical training schedules lead to only one overuse injury?

The answer is biomechanics (structure and function of living things). Despite your similar build, you and your training partner do not have the same biomechanics. You can recognize your friend by her run if you see her ahead of you on the trail. The way we move is nearly as individual as we are, but there is an ideal pattern.

You may have had your gait analyzed at some point. Maybe it was the 17-year-old working at the shoe store, or maybe it was someone with a little more training in functional biomechanics, but they likely pointed out some aspect of your running that isn’t efficient. Perhaps you’ve tweaked your running gait: switched from a rearfoot strike to a forefoot strike, or maybe shortened your stride. No matter what, changes you make in your gait can be effective only if you have the biomechanics to back them up.

If you cannot control internal rotation of your femur due to poor stability of your glutes, your knee is going to crash into valgosity with every stride, causing undue wear and tear on the medial portion of your knee, no matter what part of your foot you strike on or how short your stride is. Translation: if your knee does not stay straightforward while you run, but instead travels toward your other leg, you’re likely in for a painful “overuse” injury.

The problem with the term “overuse injury” is that it is a myth. If overutilization was truly the issue, there would be scientific backing regarding how much is too much. There are no studies (at least not to my knowledge – and I’ve looked) that state that a maximum number of miles per knee exists. Your body is not a car. It doesn’t wear out after a certain number of miles. Your body can heal, change and grow. That’s the difference between the mechanics of a car and the biomechanics of a human body.

The problem is not that your training partner has underused her body while you have overused yours. Her biomechanics just happen to be better than yours. That doesn’t mean you’ll be plagued with overuse injuries until you convert into a couch potato; it means that you need to address your biomechanical insufficiencies. You might not know you have any until you get assessed by a professional, but here are a few simple tests you can do that can point out potential issues:

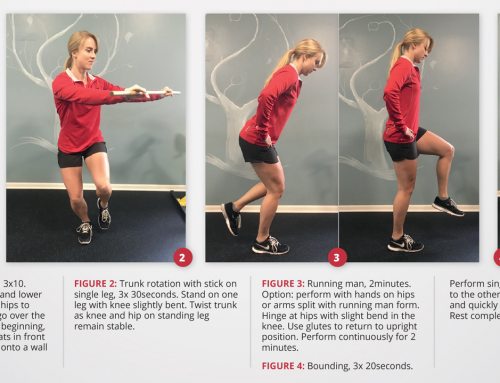

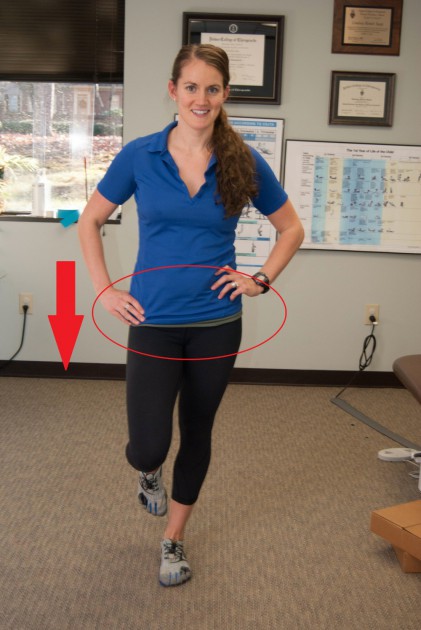

One-Legged Stand

Stand on one leg while looking in the mirror. Do you shift your weight or drop your hip in order to balance yourself, or are you able to maintain balance without shifting? Running is essentially alternating which leg you’re standing on, so if you can’t stand on one leg without moving, you can expect problems to arise when you’re doing it repeatedly.

Squat Test

Stand with your feet slightly wider than shoulder-width apart with a PVC pipe or dowel rod behind your back vertically, holding one end behind your head and one end behind your low back. Keeping your heels on the ground, squat until your hips are below your knees while holding onto the pipe. Are you unable to hold on, or do your feet turn out excessively (more than 45 degrees)? This demonstrates a lack of thoracic spine and/or ankle mobility, which can easily lead to low back pain and knee or foot pain, respectively.

6-Inch Step Down

Stand on something that is approximately 6 inches high. Stand on one leg with your toes pointing straight forward and not gripping the end of the box. Slowly lower the opposite leg down until your heel touches the floor. Can you do this without your knee bending toward the opposite leg and without your heel lifting off the box?

If you fail any of these tests, it doesn’t mean you can’t run anymore. It means you should be evaluated by someone who understands functional biomechanics (such as a DC or a PT) and ideally has experience successfully treating runners.

# # #

Dr. Lindsay Mumma is the owner of Triangle Chiropractic and Rehabilitation Center in Raleigh. She focuses on improving function and performance and offers a variety of treatments in her office, including adjustments, myofascial release and gait analysis. Visit www.triangleCRC.com to find out more or to schedule an appointment.