By Brian Schiff

Most runners would be thrilled to achieve faster times and improve running efficiency without training harder or doing more hill work. In my profession, I analyze movement and running form on a regular basis for runners of all ages and abilities. A common physical issue I see is poor hip mobility in terms of leg separation during gait. The term used to describe this separation in the training and rehab world is disassociation.

Why does hip disassociation matter? Simply put, a lack of ideal separation can negatively impact step and stride length, reduce propulsion and create other compensations that increase energy expenditure and reduce overall running form. Some of the deviations that may occur include hip drop, increased external rotation of the leg, excessive torso rotation, increased knee flexion and diminished stride length.

If you are seeking to run faster and expend less energy (a goal all runners share) then optimizing hip mobility should be a priority. The first step to achieving appropriate hip disassociation is getting a baseline assessment. In the clinic, I routinely observe hip flexor and hamstring flexibility on both sides in addition to scoring the active straight leg raise movement as part of the Functional Movement Screen (FMS). Often, I find asymmetry on one side or limited mobility on both that needs to be addressed.

Keep in mind during running that maximal hip separation is generally occurring as the trail leg is in the final phase of push-off and approaching the float phase of running. Examining the propulsion and swing phase of gait will yield clues about disassociation. Limited mobility will affect trunk movement and perhaps impact loading response. What may feel normal to the runner often presents as asymmetrical on video analysis. Marked asymmetry will increase the chance for overuse injuries.

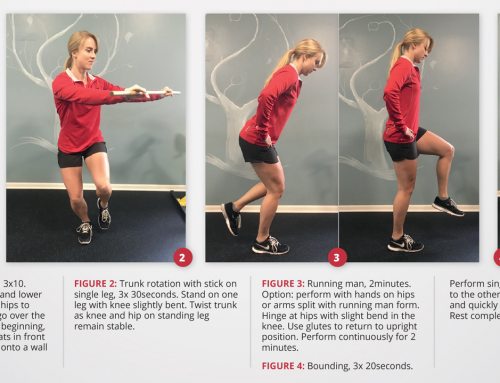

The following exercises are effective corrective techniques that can be integrated into a daily exercise routine to improve hip mobility and disassociation:

Supine leg lowering – Lie on your back using a doorway, flexing both hips and extending the knees. Place one foot on the wall with hip flexed and knee extended for a slight stretch. The other leg should be placed in a similar position without support. Next, point the toes of the unsupported leg and reach out toward the ceiling. Slowly lower the leg to the floor, maintaining a neutral lumbar spine (a bolster may be placed beneath the leg if needed). Perform 5-10 repetitions and repeat 2-3 sets on each side.

Hip lock bridge – Lie on your back and pull one thigh toward the chest to lock it (thigh should remain in contact with the chest throughout). The opposite foot should be placed on the floor in line with the center of the body with the knee flexed. Next, push down through the foot on the floor and extend the hips, bringing the pelvis off the floor. Limit the height of the bridge so that the hip and thigh remain against the chest, while the extended hip and thigh remain in proper alignment. Perform 2-3 sets of 10 repetitions on each side.

Focus on maintaining strict form at all times. These two movements may prove even more beneficial in combination with soft tissue therapy techniques for the hamstrings and hip flexors using a foam roller, stick or trigger point ball.

# # #

Brian Schiff, PT, OCS, CSCS is a sports physical therapist and supervisor at the Raleigh location of Athletes’ Performance at Raleigh Orthopaedic. The Raleigh and Cary Athletes’ Performance locations currently offer free injury screens for runners, cyclists and triathletes. For more information, visit www.apcraleigh.com or www.apccary.com.