By Bill Kraus

People often ask what types of exercise, how much and how hard, should I exercise to maintain health? What is the best exercise regimen for my health? How little exercise can I get away with? Is walking as good as running?

Because they get a lot of attention and sell newspapers and magazines, articles on exercise appear regularly in the press. Articles often contain recommendations and enticing tidbits of “wisdom” based upon misinformation and poorly validated findings. However, there is a lot of good information available; we will confine ourselves to that information.

So, we know about the different types of exercise: aerobic/cardio, resistance/strength, high intensity interval training, and flexibility. If maintaining health is the goal, and not necessarily maintaining a fitness or strength level for competition, there are several variables to consider.

In 2008, the US government released the Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans, available at health.gov/PAguidelines. The six hundred-page science document accompanying the Guidelines contains a wealth of science about the benefits of exercise in health and prevention of disease in a broad range of systems and conditions: cardiovascular diseases, cancer, weight gain, muscle and bone health, diabetes and metabolic diseases, among many others.

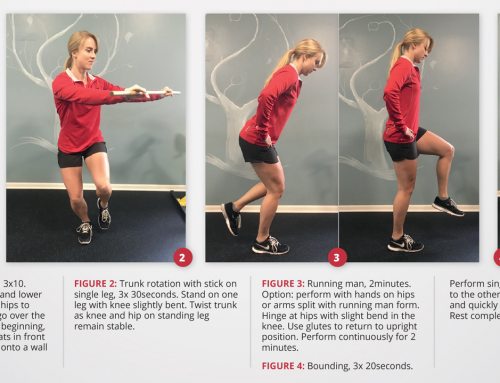

The guidelines are based on a common recommendation for the common good: 150 minutes per week of moderate intensity exercise (brisk walking) and 75 minutes of vigorous intensity exercise (“jogging”), or some combination thereof, spread over most days of the week; add in strength training at least two days of the week and some flexibility work. This is the minimum amount for health benefits for the majority of individuals; more is usually better. Individuals vary in the benefits they get from the same “dose” of exercise; some people require more or less exercise than others to get the same benefit. Some of this is driven by our genetics. Developing markers identifying people at the extremes, exceptional responders and non-responders, is an area of intense study. We call this personalized exercise prescription.

Similarly, the same exercise is not best for all conditions. Over the last several years, we have begun to realize the benefits of moderate intensity exercise over harder, more intense exercise for some conditions. It appears that for control of blood glucose and prevention of diabetes, brisk walking is equal to or better than jogging when doing the same overall distance. For improving or maintaining cardio fitness, more intense exercise, even interval training, is better than walking. The overall distance covered is important. In almost all instances, doing more of the same type of exercise is better than less.

For muscle strength, mass and health, resistance exercise rules! Note that the Physical Activity Guidelines recommend a combination of aerobic and resistance training, for a good reason. A number of years ago, we observed that a low amount of walking improved blood glucose control only modestly; and resistance exercise had almost no effect; but a combination program had a profound effect on glucose control.

One point of misinformation is the claim that resistance exercise can help prevent weight gain and obesity, because muscle is more metabolically active than fat. First, resistance exercise does not replace fat with muscle. Further, the amount of muscle gained, even with the most active strength-training program, does not result in enough change in metabolic rate to be able to be detected with our current means.

What about walking and 10,000 steps? Well, it turns out, when one accounts for the total energy expended with the recommended physical activity in the Physical Activity Guidelines, and the normal amount of activities of daily living, the result is about 10,000 steps per day.

To summarize, the type of exercise and the intensity depends on one’s health goals; some exercise modes are better for some conditions than others. With respect to health benefits, individuals respond differently to the same regimen and intensity. Getting 10,000 total steps per day, including your exercise, is a good place to start. The Physical Activity Guidelines are the minimum for general benefits across a range of health parameters; some day, hopefully soon, we will be able to personalize exercise prescription for health. In the meantime, read the Guidelines document to find out what exercise is best for your condition.

# # #

Bill Kraus is a preventive cardiologist. His research focuses on defining what exercise mode, intensity and amount results in optimal health benefits for any given individual: personalized lifestyle medicine. Also, he is committed to understanding the value of regular physical activity, regular circadian rhythm and energy balance for health benefits. Duke has a lifestyle program called Sports Medicine Forward and can measure your resting energy expenditure; exercise energy expenditure; whether you are in energy balance; how many steps per day that you get; and give you an exercise prescription for your own personal health goals and needs.