In his book It’s Not About the Bike Lance Armstrong wrote about his post-cancer ride up North Carolina’s Beech Mountain, a crucial stage in his two Tour du Pont victories. As he neared the summit, the words Go Armstrong in faded paint still visible from the old race, passed beneath his pedaling feet. It marked the beginning of one of the greatest comebacks in sports history.

Now, cycling fans across the world debate whether he has what it takes to come back one more time and win the world’s greatest cycling event. While Armstrong says his comeback is not so much about winning the Tour de France as it is about increasing cancer awareness around the world, we all know that winning is hard-wired into his genetic code. It’s hard not to imagine him winning.

Some of us however, have never won. I’ve never won. It’s a sore point with my competitive five-year-old and many of the neighborhood children who see me ride my bike down the street every Saturday morning. Five year olds… they’re always needling me with their stream-of-consciousness questions:

Did you win? Why not? Did you get a flat? What about second place? Why do you keep racing if you never win? Are you doing it right? Is your bike broken? Were you last? Do you ever win? How many people finished ahead of you? Were you sick?

And of my all-time favorite…

When are you going to “bring home some hardware”?

Then, as quickly as their questioning of my inability to win starts, it ends, as my five-year-old audience comes to agreement that I will win my next race. Why else would I still be training, they rationalize. I want to lecture them about not placing too much importance on winning, but the importance of winning, it seems, is hard-wired into the genetic code of five-year-olds, just as much as it is in Armstrong. It’s hard for five-year-olds to not imagine winning.

Unfortunately, it’s easy for many adults to imagine not winning and I can only believe that it’s because too often we frame our success based racing. While winning is not as hard-wired into everyone like it is Armstrong (and five-year-olds), we do share the same type of obstacles – some physical, some emotional, and still some political. Those new barriers, however, have not stopped Armstrong from re-engaging in life as new and improved versions of his former self.

There is nothing stopping you from doing the same.

You might not have the same supporting team as Armstrong, but you do have the power to make your own comeback, just like him. Given North Carolina’s history in fostering cycling comebacks, we suggest you do the same – become a better cyclist this year. Or, better yet, become a cyclist this year.

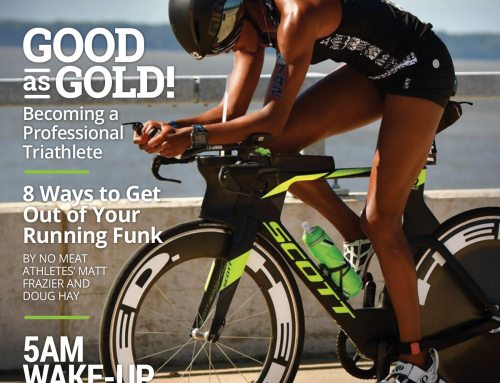

Like triathlon and running, cycling has a broad spectrum of events for you to consider. Becoming a cyclist could be joining the local Tuesday afternoon ride, or it could mean training for a national charity event ride, or maybe a local road race or Criterium.

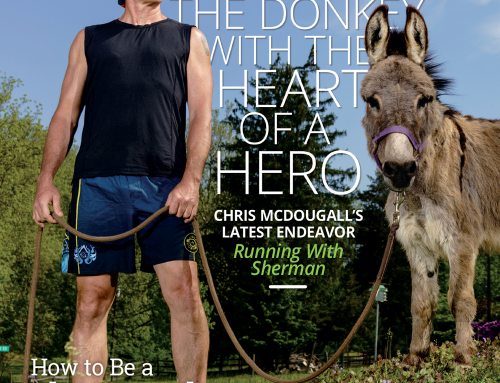

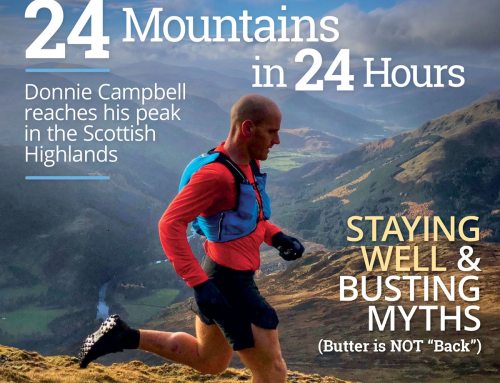

In this CYCLING edition of Endurance Magazine, we look at the stories of a college cyclist returning once again to the 24 Hours of Booty to ride in honor of his brother who died from a brain tumor and a middle-age father of five who hopes to continue his evolution as a new and better cyclist in 2009 by drawing upon the high-performance resources available to cyclists in our community to become a faster road racer and hopefully jump from a CAT 5 to CAT 4 cyclist.

Oh yes, and just in case you have a neighborhood of five-year-old fans expecting you to “bring home the hardware”, we brought in sports psychologist Michelle Joshua to explain how to frame your comeback with realistic expectations. While we can’t promise Joshua’s premises will hold up to the scrutiny of a competitive five-year-old, you shouldn’t worry. There’s probably a lesson to be learned from that rock solid faith in winning, anyway.